In 1611, a little more than a year after Galileo published the celestial discoveries he'd made through his telescope, he joined a debate about floating bodies. Ice raised the question, since Galileo's contemporaries believed ice to be heavier than liquid water, despite the fact that it floated. They attributed ice's buoyancy to its flat shape, abetted by water's resistance to penetration.

Galileo countered that ice must be less dense than liquid: Ice of any shape stays afloat, while ice forcibly submerged in water resurfaces with no apparent resistance.

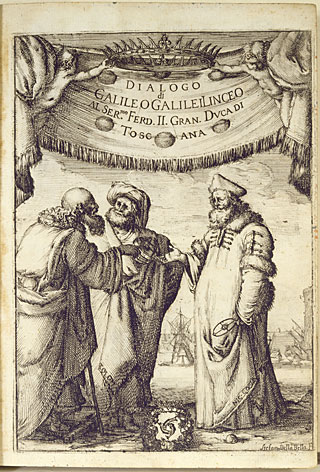

To the modern ear, the issue sounds trivial and easily decided, but Galileo's view of ice as rarefied water threatened to unravel the prevailing philosophy of science. Therefore the discussion spread from a friend's home to a wider argument with angry contenders, numerous publications on both sides of the issue, and Galileo's defense of his position in a staged debate at the Medici court.

Last July, an international group of scientists assembled in Florence to reopen the debate because, as Barry Ninham, one of the organizers, told me via e-mail, "Galileo's topic, 'Why Ice Floats on Water,' is still not resolved." Mistakes were made on both sides. The behavior of water raises more questions now than it did then.

The meeting, called Aqua Incognita, convened in a convent for five days and drew some twenty participants from Australia, Europe, Israel, Japan, Russia, and the United States. The proceedings are soon to be published as Aqua Incognita: Why Ice Floats on Water, and Galileo 400 Years On. Topics include the properties and structure of water, water's role in biology, and the effects of light and magnetic fields on water.

"Our debates were informal and our participants were limited to 20, with occasional attendance by wives and non-specialists, as for the original debates 400 years ago," write Ninham and co-editor Pierandrea Lo Nostro in the volume's introduction. "Florence itself has many attractions, being the center of the Renaissance. So it was difficult for such a meeting to fail."

Confident that Galileo would have approved, the editors "hope these contributions will provide a useful perspective and entrée for anyone interested in water in its manifold manifestations. And an insight into the science of water for the third meeting 400 years hence."

I received an early invitation to the gathering, thanks to my account of the 1611 debate in Galileo's Daughter. Although I could not attend, Ninham and Lo Nostro have now paid me another compliment by mentioning me in their book. They dedicate Aqua Incognita to the late Enzo Ferroni, whom they describe as "the pioneer in Italy of Physical Chemistry of Colloids and Interfaces, and after the 1966 flood of Florence the first scientist to apply the science of colloids and interfaces to the restoration and conservation of works of art. And to Dava Sobel for her marvelous book, Galileo’s Daughter, which gave us the human side."